The Effectiveness of Opioid Maintenance Treatment in Prison Settings a Systematic Review

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Implementation of opioid maintenance treatment in prisons in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany – a top downwards approach

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume xv, Article number:21 (2020) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

Opioid Maintenance Treatment (OMT) is a well-evaluated treatment of opioid utilise disorder (OUD). Peculiarly, nether the status of imprisonment, OMT is a preventive measure out regarding infectious diseases such as hepatitis C. Yet, simply a minority of prisoners with OUD are currently in OMT in numerous countries. In 2009, the Ministry of Justice of the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), Germany, launched the process of implementing OMT in prisons with various elements (e.g. development of recommendations regarding the handling of prisoners with OUD, monitoring the number of prisoners in OMT, education of prison doctors). In the recommendations OMT was defined as the gold standard of treatment of OUD.

Methods

To assess the effectiveness of the implementation strategy a survey on the prevalence of OMT in prisons in NRW was carried out twice a twelvemonth past the Ministry of Justice between 2008 and 2016. Participants were prisoners in NRW, Deutschland. The diagnosis of OUD at admission to prison and the treatment state on survey dates was measured.

Results

The number of prisoners in NRW dropped from 17,301 in 2008 to xvi,432 in 2016. In the same menstruum, the number of prisoners with OUD (mainly males) dropped from 4201 persons to 3650 persons and the number of prisoners in OMT increased from 139 persons (iii.iii%) to 1415 (38.seven%) persons.

Discussion

Currently, the percentage of prisoners with OUD in OMT in NRW is almost reaching the treatment rate outside prisons in Deutschland (45–50%). However, afterward release from prison house there is still a high risk for a discontinuation of OMT.

Conclusions

Overall, the tiptop-down approach of implementing OMT in prisons in the federal state of NRW was effective.

Background

Substance use disorder is one of the leading problems in the international field of health-intendance [1]. An estimated quarter of a billion people, effectually 5% of the global developed population, used drugs at least once in 2015 and of those drug users 29.5 million, 0.6% of the global developed population, suffered from a drug use disorder [2]. Opioid use disorder (OUD) in item is associated with a high mortality rate and a loftier burden of disease [three]. The number of people with OUD in Frg has been estimated about 146,580–174,064 persons [4]. Later several years of subtract, the number of drug-related deaths (DRD) in Deutschland has increased once more since 2012 to 1272 DRDs in 2017 [5].

According to current concepts, OUD is a disorder with a chronic course [6]. Abstinence-oriented treatment has only a limited success in the treatment of OUD. Therefore opioid maintenance handling (OMT) has been established. Its major aim, the reduction of the use of illegally acquired heroin, is well proven [7]. In addition, OMT lowers the hazard of the transmission of infectious diseases such every bit hepatitis C or HIV by reducing needle sharing; patients in OMT report a college well-beingness and a amend social functioning; the rate of drug-related crimes decreases for patients in OMT; patients in OMT have less stress because the force per unit area to proceeds drugs is substantially reduced; and patients in OMT were found to have reduced mental and physical comorbidities [8,9,ten,xi]. Hence, OMT has go the gilded standard of treatment of patients with OUD in many countries. In 1991, OMT was legally accepted equally a treatment in Frg and its costs are covered by the statutory health insurances [12]. The number of patients in OMT in the customs increased from approximately 52,700 in 2003, to 74,600 in 2009 up to 78,800 patients in OMT in 2017 [xiii]. Currently, the rate of people affected past OUD in maintenance treatment is almost 45–50% in Germany.

Many prisoners suffer from OUD and compared to the community, people, who employ drugs are fifty-fifty over-represented in prisons [fourteen]. According to estimates, 30% of all male prisoners and 50% of all female person prisoners in Germany inject drugs [xv]. Despite rigid controls, drug consumption occurs in prisons [16]. The condition of imprisonment favours risky behaviours due to concentrated at-risk populations and take a chance-conducive weather condition such every bit violence or overcrowding [17]. In an Irish prison population, significantly more needle sharing was skilful during imprisonment compared to the month before imprisonment [18]. Due to the high prevalence of OUD amid prisoners and the specific health risks in this environment OMT for prisoners is recommended. However, in numerous states a systematic implementation of OMT in prisons is withal lacking [19]. OMT in prison settings has basically the aforementioned aims and effectiveness as OMT in the community [20], particularly preventing the spread of hepatitis C and HIV-infection due to reduced heroin injecting and needle sharing; reduction of violent behaviour in prisoners with a substance utilize disorder [21]; reduction of heroin apply during imprisonment; reduction of the risk of dying immediately after release due to an overdose and increasing the run a risk of continue OMT upon release [22, 23].

The World Health Organization recommends OMT in prisons as standard treatment [24]. In Federal republic of germany, the costs of the medical treatment of prisoners are covered by the ministry of justice of the respective federal state during imprisonment. Co-ordinate to the principle of equivalence prisoners have a legal entitlement to receive the treatment during imprisonment which would exist covered past statutory health insurances, if the persons were exterior prison. This principle is also integrated in article 40.two in the "European Prison house Rules" [25]. Whereas the principle of equivalence seems to be effective in the handling of e.g. diabetes mellitus and hypertension, only a minority of people with OUD in German prisons have been in OMT for the last decade, although no official statistics are available regarding this topic. According to the German language Prison Act in 2006, the 16 federal states of Federal republic of germany have the legislative competence of the penal organization [26]. Therefore, all federal states are independently responsible for providing adequate medical intendance (including OMT) for prisoners.

North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) is the most populous federal country of Frg with about xviii one thousand thousand inhabitants. Given the depression rate of OMT in German prisons, the Ministry building of Justice of the federal state NRW launched the procedure of implementation in 2009. It has several elements:

Development of recommendations for the treatment of prisoners with OUD: The recommendations were adult by a task force consisting of representatives of the boards of physicians of Due north Rhine and of Westphalia, respectively, directors of prison hospitals in NRW, prison doctors, and representatives of the Ministry of Justice NRW. The evolution of the recommendations was based on the guidelines of the High german Lath of Physicians [27], which explicitly betoken out the possibility of OMT in prisons. The target group of the recommendations were prison doctors as well as prison house directors, who are responsible for the financial and personnel resource. The recommendations lay importance on the following aspects: OUD requires handling. Since OUD continues during imprisonment, treatment has to be established or continued during imprisonment. OMT is a standard and well proven handling, therefore it should exist likewise carried out in prison house according to the principle of equivalence. The recommendations entered into force every bit from Jan 15th, 2010 [28]. Information technology was a potent statement of the Ministry of Justice that it expects that OMT is carried out in prisons. The recommendations were elaborated in a mixed group including three prison house doctors to strengthen its impact on the grouping of prison doctors.

Teaching: As a specific medical qualification is required in Frg to carry out OMT ("Suchtmedizinische Grundversorgung" meaning "basic intendance for substance apply disorders"), prison house doctors were asked by the Ministry of Justice to attain this qualification past completing a grade of 50 h. In addition, the recommendations were presented and discussed at a mandatory workshop for all prison house doctors in 2010.

Monitoring: In principle, physicians in the community and in prisons are costless in the pick of a handling for an private patient in Germany. In consequence, there are no directions of the Ministry of Justice or the prison directors to prison doctors how to care for an individual prisoner. Therefore, after the proclamation of the recommendations in that location was no routine ministerial check at the level of individual prisoners with OUD, why they do not receive OMT. Rather a monitoring by the Ministry of Justice was established regarding the number of prisoners with OUD and the number of prisoners in OMT. These figures had to exist reported by each prison house twice yearly. In this style, the charge per unit of prisoners in OMT was regarded as a criterion for the quality of treat people with OUD in a given prison. The data were presented and discussed at the mandatory meetings of prison doctors organized by the Ministry of Justice one time yearly.

As the recommendations evaluate OMT as the gold standard of the handling of OUD, at that place is a lack of quality of care if only unmarried individuals with OUD in a prison house are in OMT. This evaluation does not interfere with the right of physicians to state the indication for OMT for an individual person. In addition, after the announcement of the recommendations the prison doctor could exist asked in case that an private prisoner complains about not receiving OMT, why he did not carry out the gold standard treatment in this case.

The aim of this study is to assess the effectiveness of the implementation strategy for OMT in prison. We hypothesized that the number of prisoners with OUD in OMT would increment during the monitored period.

Methods

In the federal state of NRW, Germany, there are 62 prisons with upwards to 18,500 prisoners located. In club to appraise the result of the described implementation process (and as role of this process), a survey was carried out twice a year (April and October) over the years of 2008–2016. The survey gathered data on the number of prisoners at the respective dates over all prisons in NRW, the number of prisoners with OUD, and the number of prisoners currently in OMT (methadone or buprenorphine). The twice-yearly written report was carried out by dissimilar staff members of the participating prisons, e.g. prison doctors, social workers, or other professionals of the medical service. Information were centrally gathered and analysed at the Ministry of Justice NRW. The corresponding prison physician diagnosed OUD based on a diagnostic interview held at the admission to prison house. In Germany, OUD is diagnosed co-ordinate to the diagnostic criteria of the ICD-x. In addition, a drug urine screen was carried out in order to find use of heroin and of other substances (i.e. methadone, cocaine, cannabis, amphetamine, and benzodiazepine). Since 2017, a nationwide survey on OMT in prisons in Frg has been established which replaces the former survey just in NRW with slightly dissimilar methods.

Every bit a role of OMT in prison house, psychosocial interventions are offered. These differ between the participating prisons. Nonetheless, every institution provides counselling for OUD, where prisoners can obtain information or advice if required.

Results

The number of prisoners in NRW dropped from 17,301 (in 2008) to 15,781 (in 2017) at the qualifying dates for the survey. There were statistically significantly fewer prisoners in 2017 compared to 2008. A chi-foursquare test of goodness of fit was performed to make up one's mind whether the number of prisoners was every bit distributed betwixt the years. The number of prisoners was non equally distributed, χ2 (one, N = 33,082) = 69.84, p < .01. At the respective dates, the number of prisoners with OUD also decreased significantly from 4201 in 2008 to 3650 in 2016 (χ2 (1, N = 7851) = 38.67, p < .01). In the period from 2008 to 2016, the number of prisoners in OMT increased from 139 persons out of 4201 prisoners with OUD (OMT rate: three.3%) to 1415 out of 3650 prisoners with OUD (OMT rate: 38.8%). In 2017 the number of prisoners in OMT increased fifty-fifty further to 1603 (see Tabular array 1). In 2016, there were significantly more than prisoners with OUD in OMT than in 2011. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine if OMT increased over time after the recommendations came into issue. The year 2011 was compared to 2016. Equally reference year, 2011 was chosen considering information technology was the yr later on the recommendations of OMT in prison had entered into strength and 2016 was called because information technology contained the most recent data. The relation between these variables was meaning, χii (one, N = 8391) = 168.87, p = <.01.

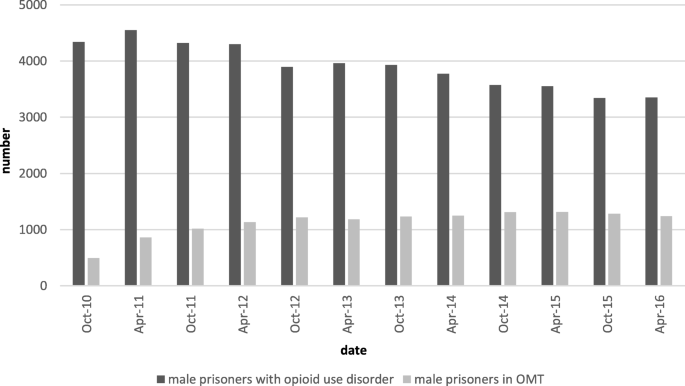

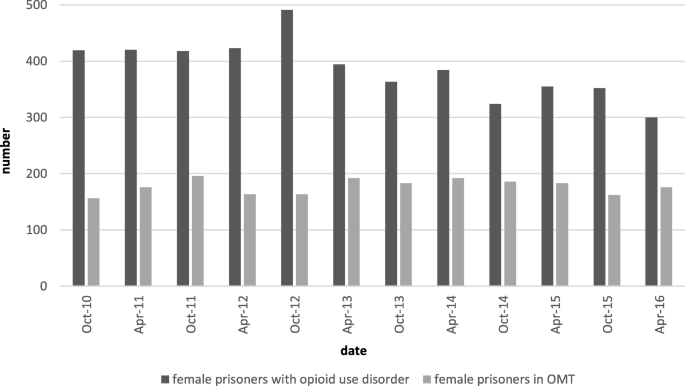

Prisoners with OUD were mainly male [in 2016: 3350 males (91.8%) and 300 females (8.2%)]. The proportion of male person prisoners in OMT increased over the years from eleven.4% in 2010 to 37.0% in 2016 (see Fig. i). The proportion of female prisoners in OMT was already relatively loftier in 2010 with 37.ii% (see Fig. 2). The number of female person prisoners in OMT was stable during the observation menstruation, although the total number of female person prisoners with OUD decreased. Therefore, the proportion of female prisoners with OUD in OMT increased up to 58.7% in 2016 (run across Fig. 2).

The proportion of male person prisoners with opioid apply disorder in opioid maintenance treatment

The proportion of female person prisoners with opioid use disorder in opioid maintenance treatment

Give-and-take

The data emphasize that the procedure of implementation of OMT in prisons in NRW was very effective. Currently, the percent of prisoners with OUD in OMT in the federal land of NRW (38.7%) is about reaching the treatment charge per unit (well-nigh 45–50%) in the community in Germany. The effectiveness of the implementation process is based on several elements: the clear statement of the Ministry building of Justice that OMT has to be implemented in prisons, treatment recommendations developed by the medical profession defining a standard of care, medical education of prison doctors regarding substance use disorders, and a monitoring system near the implementation of OMT.

Furthermore, the number of prisoners in NRW dropped from 17,301 to 15,781 on the qualifying survey dates. At the same time, the number of prisoners with OUD decreased from 4201 to 3650. An explanation for a reduction of prisoners with OUD in the studied time period might be a reduction of heroin-related offences in Germany. The overall number of drug-related offences increased from 231,007 in 2010 to 352,320 in 2018, whereas drug-related offences with relation to heroin decreased from 24,574 in 2010 to 11,402 in 2018. Since drug offences are among the chief offences of people with OUD, this might be a fractional explanation for a reduction of prisoners with OUD [29]. The number of people with OUD in the German population has been rather stable over the last twenty years in Deutschland [30].

Furthermore, in 2012, the Federal Chiffonier adopted the National Strategy on Drug and Addiction Policy in Germany. The strategy aims to assist individuals avoid or reduce the consumption of substances and is based on prevention, treatment, harm reduction measures, and repression [31]. The adoption of this new strategy might accept had an influence on reducing the number of prisoners with OUD.

We as well institute a deviation between male person and female person prisoners in OMT. The proportion of male prisoners in OMT increased over the years from 11.4 to 37.0%. The proportion of female prisoners in OMT was already relatively loftier in 2010 with 37.2% and remained rather stable during the following ascertainment catamenia.

A nationwide survey in German prisons found that female prisoners use opioids more often than male prisoners and that 34% of female prisoners had OUD compared to 19% of male prisoners [30]. Furthermore, this report confirms that more female person prisoners were in OMT in prison: in 2018, 21.4% of male prisoners were in OMT and 53.6% of female prisoners were in OMT. Since our results for the federal country of NRW are in line with the results of the nationwide survey, they exercise non stand for a specific effect for this detail federal land. A study of OUD in the German population estimated that 62.02% of females with OUD and 54.96% of males with OUD are in OMT [32], showing that females with OUD are generally more than often in OMT.

Despite the effectiveness of the process of implementation, the majority of prisoners with OUD in NRW are still not in OMT. However, most half of the people with OUD in the community are too non in OMT in Germany. In that location may be unlike reasons for patients staying out of OMT. Firstly, OMT is a difficult option for patients, who might fear treatment rules [9, 33]: Drug urine screens regarding non only heroin, but also mayhap concomitantly used drugs are a handling requirement in OMT in Deutschland. Concomitant utilise of other drugs tin can endanger the continuation of OMT in the community besides as in prison. Other requirements include a medically supervised administration of the daily dose of the maintenance medication and reliable compliance attending appointments with the treating physician and the social workers. For some patients this might seem impossible to achieve. Negative experiences with treatment, like side-furnishings such as sedation under methadone, episodes of OMT without success, as well every bit a lack of information may exist additional reasons for staying out of OMT [17, 33]. In addition, patients might fear to become unable to withdraw from the maintenance medication [34]. Furthermore, prison inmates might wish to use the time in prison to go abstinent from all substances and might fright the long-term nature of OMT [35].

Moreover, the part of stigmatization for the implementation of OMT in prison should be emphasized. Fifty-fifty though OMT has been officially accepted equally the golden standard handling of OUD, it continues to be stigmatized. 78% of a study sample of patients currently in OMT reported having experienced stigma related to OMT [36]. Some people believe that people with OUD use OMT to get high, that OMT patients are incompetent, unfit to work and untrustworthy, and that people with OUD simply have a lack of willpower to overcome their disorder. In sum, a poor agreement of OUD as a chronic, relapsing disease is mutual. One explanation for the depression implementation of OMT in prisons might be that stigmatizing attitudes could exist also common in prison doctors, directors and other persons involved in planning and carrying out health care in prisons. In this context, it is noteworthy, that in the surveys at the qualifying dates the maintenance rates betwixt the prisons varied largely. For instance in Apr 2015, the rates were betwixt 12 and 80% (only analysing prisons with at least 20 prisoners with the known diagnosis of OUD). Too of interest is the fact, that in order to receive OMT, 40 prisoners in Würzburg (federal state of Bavaria) went on a hunger strike in July 2016. The hunger strike ended unsuccessfully after xi days [26]. The European Court of Human Rights stressed in its decision of September 1st, 2016 in a case against the Federal Commonwealth of Germany the principle of equivalence in the care of prisoners suffering from OUD [37].

Even though the number of prisoners in OMT increased during the last years in NRW, at that place is the trouble of continuity of OMT. This might regard the continuation of OMT at admission to prison as well as upon prison house release. Too the fact that an abrupt catastrophe of OMT at imprisonment conspicuously offends confronting the legal principle of equivalence, this can exist physically and psychologically lamentable for the imprisoned patients [38] and even unsafe, since withdrawal symptoms accept been found to exist a trigger for suicide during the offset week of prison [23]. In addition, the continuity of OMT in prison and after release is of high importance: Because of intervals of abstinence during imprisonment, the tolerance for drugs is reduced, meaning that a smaller dose tin can already event in life-threatening conditions [39]. A review by Hedrich et al. [20] revealed that pre-release OMT was highly associated with an increase in both, handling uptake and retention after release. Sponsored by the Ministry of Health NRW, there is at present an ongoing study to improve continuation of care, specially OMT, in the customs after release from prison.

The post-obit limitation of the report has to exist discussed: The diagnosis of OUD is based on the diagnostic interview carried out by the prison doctor at access of a prisoner to the prison. In addition, a drug urine screen is carried out in lodge to detect use of heroin and of other drugs. Every bit the diagnostic criteria of OUD are mainly based on data given by the prisoner in that location might the risk of underdiagnosing OUD. Even so, the rates of prisoners with OUD out of all prisoners in NRW are within the range known from other federal countries in Deutschland [40]. In addition, there is no uncertainty that the charge per unit of prisoners in OMT increased substantially in the observation period.

Conclusions

Overall, our piece of work has led us to conclude that the tiptop-down approach of implementing OMT in prisons in the federal state of NRW was effective. Information technology seems that the clear statement of the Ministry building of Justice that OMT has to exist implemented in prisons as well as treatment recommendations developed by the medical profession defining a standard of care, medical education of prison doctors and a monitoring system were important parts in increasing the amount of prisoners in OMT. The percentage of prisoners with OUD in OMT in NRW has increased continuously since 2009 and is at present most reaching the treatment rate in the customs in Germany. Nevertheless, the majority of prisoners with OUD are not in OMT. Reasons for staying out of OMT might be fear of handling rules, negative experiences with treatment or stigmatization. Furthermore, there is still a high risk of a discontinuity of OMT at access to prison as well as upon prison house release. Time to come inquiry needs to focus on effective ways to ensure a consistent continuation of treatment in terms of the principle of equivalence.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this report are included in this published commodity.

Abbreviations

- DRD:

-

Drug-related deaths

- NRW:

-

Northward Rhine-Westphalia

- OMT:

-

Opioid maintenance therapy

- OUD:

-

Opioid use disorder

References

-

Gowing LR, Ali RL, Allsop S, Marsden J, Turf EE, West R, et al. Global statistics on addictive behaviours: 2014 status study. Habit. 2015;110(6):904–19.

-

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Earth drug report 2017. Un publication; 2017.

-

Teesson Thousand, Marel C, Darke Due south, Ross J, Slade T, Burns 50, et al. Long-term mortality, remission, criminality and psychiatric comorbidity of heroin dependence: xi-year findings from the Australian treatment outcome study. Addiction. 2015;110(half-dozen):986–93.

-

Addiction EMCfDaD. European drug report 2017: trends and developments. Luxemburg: Publications Function of the European union; 2017.

-

Dice Drogenbeauftragte der Bundesregierung. Drogen- und Suchtbericht 2018. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit; 2018.

-

Hser Y-I, Hoffman 5, Grella CE, Anglin Medico. A 33-yr follow-upwards of narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(five):503–eight.

-

Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli Grand. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(three):one-27.

-

Larney S. Does opioid substitution treatment in prisons reduce injecting-related HIV take a chance behaviours? A systematic review. Addiction. 2010;105(two):216–23.

-

Stöver H. Barriers to opioid substitution treatment access, entry and retentiveness: a survey of opioid users, patients in handling, and treating and non-treating physicians. Eur Addict Res. 2011;17(1):44–54.

-

Globe Health Organization. Clinical guidelines for withdrawal management and treatment of drug dependence in airtight settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

-

Michels II, Stover H, Gerlach R. Substitution handling for opioid addicts in Germany. Harm Reduct J. 2007;iv:5.

-

Bundesausschuss der Ärzte und Krankenkassen. Erweiterungen der NUB-Richtlinien. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 1991;88.

-

Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM). Bericht zum Substitutionsregister 2018. In: Bundesopiumstelle, editor. Bonn, 2018.

-

Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction. 2006;101(2):181–91.

-

Lesting West, Stöver H. Gesundheitsfürsorge, §§ 56–66, 158. In: Feest J, editor. Kommentar zum Strafvollzugsgesetz. 6. Köln: Carl Heymanns Verlag; 2012.

-

Stöver H. Drogenabhängige in Haft - Epidemiologie, Prävention und Behandlung in Totalen Institutionen. Suchttherapie. 2012;thirteen(02):74–fourscore.

-

Stover H, Michels II. Drug use and opioid substitution handling for prisoners. Harm Reduct J. 2010;7:17.

-

Allwright S, Bradley F, Long J, Barry J, Thornton L, Parry JV. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV and risk factors in Irish prisoners: results of a national cantankerous sectional survey. BMJ. 2000;321(7253):78–82.

-

Hedrich D, Farrell M. Opioid maintenance in European prisons: is the handling gap closing? Addiction. 2012;107(3):461–3.

-

Hedrich D, Alves P, Farrell M, Stover H, Moller L, Mayet Southward. The effectiveness of opioid maintenance handling in prison settings: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(3):501–17.

-

Friedmann PD, Melnick G, Jiang 50, Hamilton Z. Violent and confusing behavior among drug-involved prisoners: relationship with psychiatric symptoms. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26(4):389–401.

-

Rich JD, McKenzie M, Larney S, Wong JB, Tran Fifty, Clarke J, et al. Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: a randomised, open-characterization trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350–9.

-

Larney S, Gisev Due north, Farrell One thousand, Dobbins T, Burns Fifty, Gibson A, et al. Opioid substitution therapy as a strategy to reduce deaths in prison: retrospective accomplice report. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004666.

-

Globe Health Arrangement UNOoDaC, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (WHO/UNODC/UNAIDS). Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS prevention: position paper. Geneva: World Wellness Organisation; 2004.

-

Quango of Europe. European prison rules 2006. Bachelor from: https://rm.coe.int/16806f3d4f.

-

Wissenschaftlicher Dienst des Deutsches Bundestags. Substitutionsbehandlung im Justizvollzug - Sachstand. https://www.bundestag.de/blob/480528/079376bd958e4a1b9baa2652713d63cb/wd-9-049-16-pdf-data.pdf2016. p. fourteen.

-

Bundesärztekammer. Richtlinien der Bundesärztekammer zur Durchführung der Substitutionsgestützten Behandlung Opiatabhängiger 2010.

-

Justizministerium NRW. Ärztliche Behandlungsempfehlungen zur medikamentösen Therapie der Opiatabhängigkeit im Justizvollzug – Substitutionstherapie in der Haft. Düsseldorf: Justizministerium NRW; 2010.

-

Polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik Bundesrepublik Federal republic of germany. Jahrbuch 2018. https://www.bka.de/DE/AktuelleInformationen/StatistikenLagebilder/PolizeilicheKriminalstatistik/PKS2018/pks2018_node.html.

-

Dice Drogenbeauftragte der Bundesregierung. Drogen und Suchtbericht 2019. https://www.drogenbeauftragte.de/fileadmin/dateien-dba/Drogenbeauftragte/4_Presse/1_Pressemitteilungen/2019/2019_IV.Q/DSB_2019_mj_barr.pdf.

-

Dice Drogenbeauftragte der Bundesregierung. National strategy on drug and addiction policy. 2012; http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/organization/files/attachments/9075/Drug%20Commissioner%20of%20the%20Federal%20Government%2C%20Germany%xx%282012%29%20National%20Strategy%20on%20Drug%20and%20Addiction%20Policy.pdf.

-

Kraus L, Seitz NN, Schulte B, Cremer-Schaeffer P, Braun B, Gomes de Matos E, et al. Schätzung Opioidabhängiger in Frg. München: IFT Institut für Therapieforschung; 2018.

-

Brandt L, Unger A, Moser Fifty, Fischer G, Jagsch R. Opioid maintenance treatment--a call for a joint European quality care arroyo. Eur Addict Res. 2016;22(1):36–51.

-

Mitchell SG, Willet J, Monico LB, James A, Rudes DS, Viglione J, et al. Community correctional agents' views of medication-assisted handling: examining their influence on treatment referrals and community supervision practices. Subst Abus. 2016;37(ane):127–33.

-

Larney South, Zador D, Sindicich N, Dolan K. A qualitative study of reasons for seeking and ceasing opioid commutation handling in prisons in New South Wales, Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36(three):305–ten.

-

Woo J, Bhalerao A, Bawor M, Bhatt M, Dennis B, Mouravska N, et al. "Don't gauge a book past its embrace": a qualitative report of methadone patients' experiences of stigma. Subst Abuse Res Treat. 2017;1-12.

-

European Courtroom of Human Rights. Wenner v. Germany, no. 62303/13, § 59. ECHR; 2016.

-

Aronowitz SV, Laurent J. Screaming behind a door: the experiences of individuals incarcerated without medication-assisted treatment. J Correct Health Care. 2016;22(ii):98–108.

-

World Health Organisation Regional Function for Europe. Prevention of acute drug-related mortality in prison house populations during the immediate mail-release catamenia. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010.

-

Schulte B, Stover H, Thane K, Schreiter C, Gansefort D, Reimer J. Substitution treatment and HCV/HIV-infection in a sample of 31 High german prisons for sentenced inmates. Int J Prison Health. 2009;5(i):39–44.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

KB: article writing, statistical analysis. HS: article editing. IR: conceptualization, commodity editing. NS: conceptualization, article writing, article editing. All authors read and approved the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approval

None, no analysis of private related data, but assay of governmental statistics.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

N Scherbaum received honoraria for the participation in Advisory Boards and for holding lectures by the companies AbbVie, Sanofi-Aventis, MSD, Mundipharma, Indivior (formerly Reckitt-Benckiser), Medice and Lundbeck in the by 5 years. K Böhmer, H Schecke and I Render have nothing to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as yous requite appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and bespeak if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If fabric is not included in the article's Artistic Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, yous volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the information.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Böhmer, Yard., Schecke, H., Render, I. et al. Implementation of opioid maintenance treatment in prisons in N Rhine-Westphalia, Federal republic of germany – a top downwardly approach. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 15, 21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00262-w

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00262-due west

Keywords

- Opioid maintenance treatment

- OMT

- Prison

- Federal republic of germany

Source: https://substanceabusepolicy.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13011-020-00262-w

0 Response to "The Effectiveness of Opioid Maintenance Treatment in Prison Settings a Systematic Review"

Post a Comment